SIIM: New Reimbursement Codes Set to Advance 3D Printing

In anticipation of the unprecedented launch of reimbursement codes for medical 3D printing in July, a panel of 3D printing experts discussed the implications of this critical landmark and how it may shape future work in the field in a Thursday interactive session at the Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) annual meeting.

“3D printing has improved our collaboration, collegiality, and closeness with other working professionals.” — Dr. Jane Matsumoto

The new current procedural terminology (CPT) category III codes for 3D printing are likely to promote widespread clinical application of the technology in healthcare, not just by radiologists but by other clinicians and engineers across the hospital as well, Dr. Jane Matsumoto of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, told session attendees.

“The unique thing about 3D printing is that it’s a convergence; it isn’t just all radiology, it isn’t just all engineers, it’s not just all surgery,” she said. “To get your best models and do your best work, you take these people out of silos and bring them together in one space for the care of patients.”

![]() Reimbursement at last

Reimbursement at last

The American Medical Association (AMA) has approved four new CPT category III codes that will be available for use effective July 1:

It is important to note that the category III codes are only temporary: they have no innate monetary value assigned to them and will be paid on a discretionary basis, Andy Christensen from Ottawa University noted.

“For 20 years, we have worked to get the nomenclature in place, and now having the codes established at least gets us on the board,” he said. “We are in this period, for the next couple of years, where we will be collecting data and trying to extract clinical value in order to push forward to get permanent codes.”

Recognizing this situation, the American College of Radiology (ACR) and RSNA are collaborating on building a registry for the collection of 3D printing data in hospital settings. The goals of the registry include demonstrating growing usage of 3D printing, showing typical cases using 3D printing for distinct conditions (along with the most common types of 3D-printed models used), documenting the work required to produce models, and confirming the clinical utility of anatomic models and guides.

The category III codes serve, in a sense, as temporary place holders while the community documents widespread usage of 3D printing and eventually moves toward proving specific clinical indications that have documentable value, Christensen noted.

![]() Next steps

Next steps

Following the presentations, attendees raised several questions concerning the future of medical 3D printing, including this important one: How can clinicians receive funding for 3D printing research and applications?

RSNA has offered grants of roughly $10,000 in the past, but several radiologists have also started with modest in-house grants and then reached out to other departments with which they were collaborating, Dr. Edward Quigley, PhD, from the University of Utah Medical Center, noted.

“So, if I was working on creating a 3D model for ophthalmology, I would reach out to that department,” he said. “But as of July 1, there’s potential that this process may eventually be self-supporting. If we do multicenter work, and show that we’re decreasing mortality and morbidity, we have the potential to show the value of this technology.”

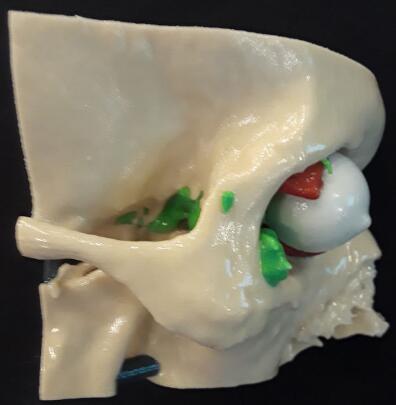

3D-printed craniofacial model

3D-printed craniofacial model depicting part of a skull (beige), a multicentric tumor (green), eye (white), and extraocular muscles (red). Model courtesy of Dr. Edward Quigley, PhD.

Regarding the future direction of 3D printing, Christensen asserted that the discipline is all about personalizing medicine. The physical nature of 3D-printed models makes sense for improving surgery and education for individual cases, he noted. 3D printing allows clinicians to get to know each patient more personally, ultimately making surgery more efficient.

Beyond traditional 3D printing, Quigley believes the most important future application of the technology lies with bioprinting. “In 10 years, I fully expect us to be pioneers of highly functioning, patient-specific bioprinting using human compliant tissue,” he said.

“Within 3D printing, there are tremendous developing opportunities in patient education, augmented and virtual reality, development of cutting guides, surface scanning research, use of artificial intelligence, etc.,” Matsumoto added. “My thought has always been that this is a tool, and you give it to really smart people in medicine, they can take it to places where they know they want it — places you can’t think of because it’s their area. It’s about getting it out there, having it available, and helping people use it.”

![]() More support

More support

Furthermore, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) plans to reimburse the 0559T and 0561T codes, providing additional support for 3D printing.

“If CMS reimburses [3D printing], that gives us credibility to go to the insurance companies and say, ‘We’re going to code these, and we’d like reimbursement for it. Here’s the data out there.’ It’s really opening a door that wasn’t there before,” Matsumoto said.

Clinicians should also make sure to document exactly what the 3D printing process entails, from the time it takes to segment and manufacture models to how much space the work requires, so that they can be reimbursed properly, she continued. 3D-printed models and guides can offer tremendous value in a variety of ways, such as improving outcomes for surgery and providing new training opportunities for residents, and it’s important to receive adequate reimbursement for them.

For example, an ongoing study led by Nicole Wake, PhD, director of 3D imaging at Montefiore Medical Center, has already evaluated the potential benefits of 3D-printed models in the management of hundreds of kidney and prostate cancer cases. The work involves contributions from a variety of disciplines, and the group plans to keep track of the specifics for each case for submission to the registry.

3D-printed kidney model containing a tumor (purple), aorta and iliac and renal arteries (pink), veins (blue), and the collecting duct system (yellow). Image courtesy of Nicole Wake, PhD.

3D-printed kidney model containing a tumor (purple), aorta and iliac and renal arteries (pink), veins (blue), and the collecting duct system (yellow). Image courtesy of Nicole Wake, PhD.

“It’ll be exciting to have our data be part of a registry, and we encourage all hospitals to take part in the registry as well as publish their data because we really need more quantitative data,” Wake said. “There are a lot of opportunities to improve image-segmentation algorithms, to understand which types of materials are best suited for different applications, and to quantify the clinical value of the models and how they are improving patient education.”

![]() Next steps

Next steps

Following the presentations, attendees raised several questions concerning the future of medical 3D printing, including this important one: How can clinicians receive funding for 3D printing research and applications?

RSNA has offered grants of roughly $10,000 in the past, but several radiologists have also started with modest in-house grants and then reached out to other departments with which they were collaborating, Dr. Edward Quigley, PhD, from the University of Utah Medical Center, noted.

“So, if I was working on creating a 3D model for ophthalmology, I would reach out to that department,” he said. “But as of July 1, there’s potential that this process may eventually be self-supporting. If we do multicenter work, and show that we’re decreasing mortality and morbidity, we have the potential to show the value of this technology.” 3D-printed craniofacial model depicting part of a skull (beige), a multicentric tumor (green), eye (white), and extraocular muscles (red). Model courtesy of Dr. Edward Quigley, PhD.

3D-printed craniofacial model depicting part of a skull (beige), a multicentric tumor (green), eye (white), and extraocular muscles (red). Model courtesy of Dr. Edward Quigley, PhD.

Regarding the future direction of 3D printing, Christensen asserted that the discipline is all about personalizing medicine. The physical nature of 3D-printed models makes sense for improving surgery and education for individual cases, he noted. 3D printing allows clinicians to get to know each patient more personally, ultimately making surgery more efficient.

Beyond traditional 3D printing, Quigley believes the most important future application of the technology lies with bioprinting. “In 10 years, I fully expect us to be pioneers of highly functioning, patient-specific bioprinting using human compliant tissue,” he said.

“Within 3D printing, there are tremendous developing opportunities in patient education, augmented and virtual reality, development of cutting guides, surface scanning research, use of artificial intelligence, etc.,” Matsumoto added. “My thought has always been that this is a tool, and you give it to really smart people in medicine, they can take it to places where they know they want it — places you can’t think of because it’s their area. It’s about getting it out there, having it available, and helping people use it.”

Source: AuntMinnie

Recent Comments